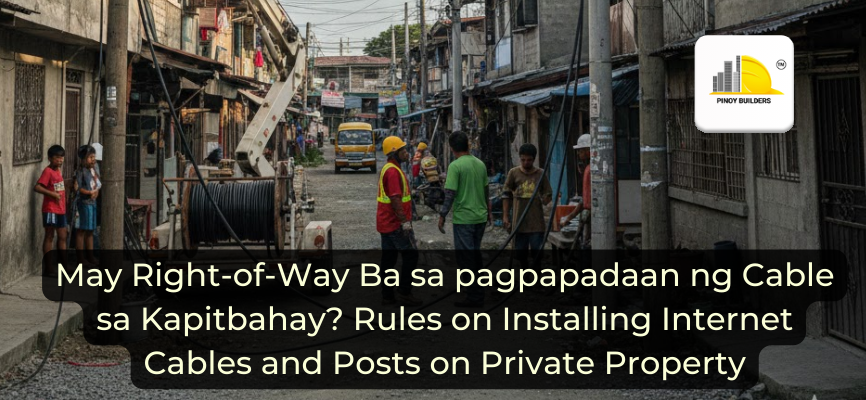

Living in a crowded neighborhood often leads to a common modern dilemma: your internet technician arrives, looks up at the poles, and realizes the only way to get you connected is to run a cable directly over your neighbor’s roof or backyard.

In this article, we will explore the legal boundaries of property ownership, the specific policies held by utility providers, and the proper steps to take to ensure your high-speed connection doesn’t lead to a high-tension dispute with the people next door.

1. Understanding “Easement of Right of Way”

In Philippine law, specifically under the Civil Code, an easement is a “burden” placed on one property (the servient estate) for the benefit of another property (the dominant estate).

While we usually think of “Right of Way” as a path for walking or driving, Articles 637 to 687 cover various easements. However, there is no automatic “free pass” for internet cables.

- Utility Easements: These are usually granted to the government or utility companies for public service on public land.

- Private Property Rights: As a homeowner, you own not just the ground, but also the space above it. This means a neighbor generally has the legal right to refuse cables crossing their “airspace.”

- The “Compulsory” Rule: Under Article 649, you can only legally demand a right of way if your property is “isolated” and has no other access to a utility line, and even then, you must pay proper indemnity (compensation) to the neighbor.

2. Utility Provider Policies (Meralco, Telcos, etc.)

To avoid legal complications, service providers like Meralco and major Telcos prioritize using public infrastructure over private land. They generally follow a “Path of Least Resistance” policy, which favors installations on government-owned sidewalks and roadsides. Consequently, these companies will often refuse to install cables or posts if a private property owner raises an objection.

- Public vs. Private: They prioritize using existing public poles on government-owned sidewalks or roadsides.

- The “Consent First” Rule: If a technician needs to plant a pole inside a private compound or run a wire that sags over a neighbor’s garden, they are strictly instructed to ask for the owner’s permission first.

- Liability: Most Telcos will refuse to install a cable if a neighbor actively objects. The company does not want to be held liable for “property encroachment” or trespassing.

3. Securing Consent: Written vs. Verbal

When the only available path for your internet signal passes through a neighbor’s property, your approach to asking is just as critical as the request itself. Establishing a respectful dialogue helps set the tone for a cooperative relationship rather than a legal confrontation. By prioritizing clear communication from the start, you increase the likelihood of securing the access you need for a stable connection.

Verbal Permission

- Pros: Fast, informal, and keeps things friendly in tight-knit communities.

- Cons: Extremely risky. If you have a falling out next year, or if the property is sold to a new owner, they can claim they never agreed to it and demand you remove the wire immediately.

Written Agreement (Recommended)

A simple Letter of Consent or a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) is the gold standard for protecting your internet connection. It should state:

- That the neighbor allows the cable to pass through a specific area.

- That you (the subscriber) are responsible for any damages during installation.

- The duration of the agreement (e.g., “for the duration of the internet subscription”).

4. Dispute Resolution: When Things Get Messy

A neighbor refusing access or intentionally cutting your existing cable can lead to significant legal and service-related complications. If your line is tampered with, you should document the damage immediately and contact your service provider to assess repair options. Ultimately, resolving such disputes often requires mediation or legal intervention to enforce easement rights and restore connectivity.

- Avoid “Self-Help” Retaliation: Do not get into a shouting match or cut their wires in return. While cutting a utility line can be considered a criminal act (Malicious Mischief), “trespassing” a wire onto their land without consent is also a civil violation.

- The Barangay Level: Most cable disputes should be settled through the Lupong Tagapamayapa. They can help draft a formal mediation agreement that is legally binding.

- Technical Rerouting: Ask your Telco if there is an alternative “drop wire” path, even if it requires a longer cable or the installation of an additional “jumper” pole on your own property.

- Offer a “Sweetener”: Sometimes, offering to pay a small one-time fee or helping repair a portion of their roof/fence in exchange for the wire placement can turn a “No” into a “Yes.”

You do not have an absolute, automatic right to pass cables through a neighbor’s private property without their consent. Clear communication and written documentation are your best tools to stay connected without burning bridges.